As I near the end of my literature review on the intersection between help-seeking behaviour and online learning environments, I can see a clear connection between my topic and the contents of EDCI 568: Discourse on Social Media for Connected and Personalized Learning. This connection is particularly strong in Yang et al.’s (2024) study which explores how students prioritize help-seeking when engaged in online learning environments. They assert that recent studies on help-seeking have been predominantly focused on face-to-face interactions rather than their online counterparts. With the proliferation of social media tools in education such as Zoom, Teams, and Moodle, Yang et al. (2024) argue that these tools can be used as an avenue for students to seek help from their peers. However, they note one important drawback: low-achieving students are often challenged by online learning due to greater need for self-regulated learning strategies; skills that are often underdeveloped in these students.

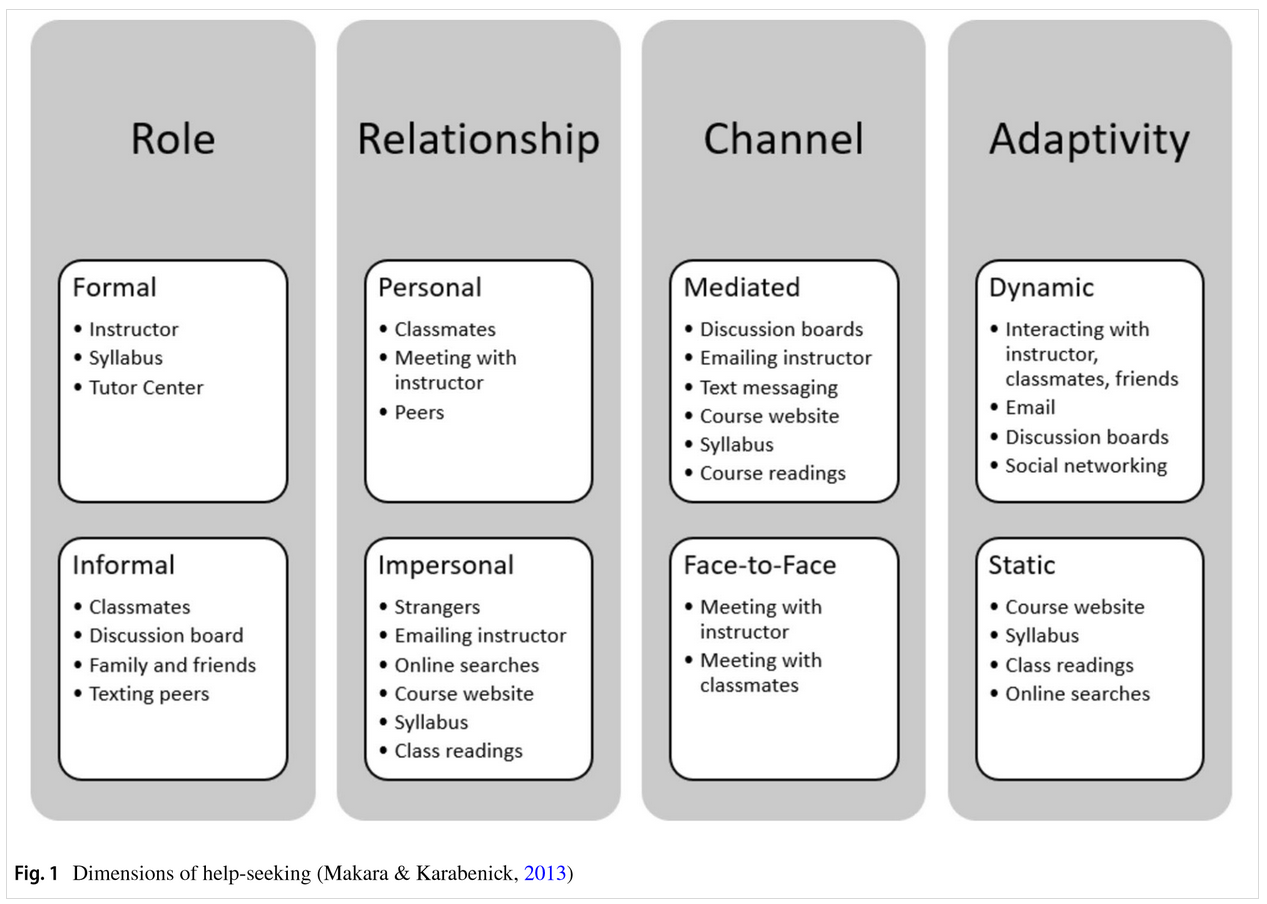

The purpose of this study was to “explore undergraduate learners’ help-seeking preferences in online settings and factors that influence their prioritization of help-seeking strategies (Yang et al., 2024, p. 459).” The framework for help-seeking they have adopted for this study is from a study conducted by Makara and Karabenick (2013) and is pictured below (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Dimensions of Help-Seeking

Makara and Karabenick (2013) assert that help-seeking behaviour can be categorised according to (a) the role of the helper, (b) the relationship between the learner and the helper, (c) the method of interaction between the learner and the helper, and (d) the dynamic nature of the help source. These categories are simply referred to as role, relationship, channel, and adaptivity in the remainder of this study.

After surveying a group of undergraduate students and applying the Q methodology, they found that three groups emerged in terms of help-seeking preference: (1) informal and personal help-seekers, (2) formal and impersonal help-seekers, and (3) technology-oriented help seekers. Learners in group 1 demonstrated a strong preference for close friends as sources of help and believed that chatting with close peers was beneficial for problem solving. Students in group 2 however were partial to instructor help as well as course websites and syllabi. These students typically prefer to context their instructor via email rather than face-to-face which is part of the reason this group is described as formal. Finally, learners in group 3 typically avoid getting help from instructors or peers because they believe that technology offers more “varied and better options“ (Yang et al., 2024, p. 463). Students in this group often complain that communications with instructors cannot provide enough timely feedback which leads them to either online sources or face-to-face tutoring centers.

The implications of this study (Yang et al., 2024) for educators are that we need to design our courses and learning environments to accommodate the help-seeking preferences of our students. From this study, we can see that learners seek help from a variety of sources such as close friends, instructors, and technology. When designing online learning environments, we need to ensure that we are not just making connections possible, but encouraging students to take advantage of varied sources according to their needs.

Personal Connection

When I look back on my illustrious career as a physics undergraduate at UVic, I definitely belonged to group 3 – technology first. I entered my first year of studies as an adult; a grizzled 25-year-old castaway from the Royal Canadian Navy. After turning bolts for a living it is perhaps needless to say that my academic confidence was at an all time low. I often did not turn to peers for academic help due to the vast age discrepancies between us and I avoided professors like the plague because I was intimidated by their infinite wisdom. What was a tarnished sailor to do? Thankfully, I found my new best friend: Chegg. Boy did this website have it all: curated solutions to homework problems, expert Q&A’s, proofreading, and so much more. Why would I ever need to approach a classmate or instructor for help when I had the powerful and all knowing Chegg at my side?

As it turns out, Chegg could not do it all. As I entered my third year of studies at the University of Victoria, it became clear that as my studies became more niche and the classes got smaller, Chegg could no longer do the job. One class in particular, differential geometry in R3, forced me out of my help-seeking comfort zone since the instructor had designed the terminology and concepts of the course. It was a rapid departure from typical math discourse since the notation and conventions lived entirely in him. With the internet now useless, I had to resort to asking my peers for help to tackle this monumental challenge and I even showed up to office hours a few times. This is, perhaps, a bad example: I dropped the course because the concepts were too elusive for me and I had accepted that the circumstances leading me to that classroom were not sufficient to pass. In other classes, this adaptation to my help-seeking behaviours proved more successful. I was able to form small study groups with similarly aged peers and I was regularly going to office hours when I needed clarification.

Throughout my four year career as a student in the faculty of science, my help-seeking behaviours shifted many times due to the resources available to me and the nature of the help required. While I matured, I took advantage of more personalized sources of help such as peers and instructors but I never left my technological preferences entirely behind. This is, in part, due to my growing confidence as a student; I finally felt like I belonged and could contribute to discussions around physics. While not mentioned in Yang et al. (2024), I think that my avoidance of in-person help stemmed from shame: I felt bad seeking help when I thought I had none to give.

Professional Connection

At the ripe old age of 29, I began my career as a teacher in part due to the meaning I find when I help others. When I first started, I thought that my most successful students would be the ones that took advantage of me as a source for help. This could not be more wrong. While one of my strongest students basically lives in my classroom and asks me questions every 12 seconds, her academic equal spends most of her time studying in groups and scouring the internet. It became clear to me that where students get help is not all that important to their success; it is if they get help that matters. In my experience, the best way to get students to seek help is to provide them with choice and opportunity. I provide students with a variety of learning experiences like group problem-solving and inquiry tasks where I give them choice when selecting resources.

Another revelation I’ve had during my short teaching career is how I help my students. Is it helpful to help my students whenever they ask for it? Is it productive if I help them in exactly the way they would like me to? In my experience, students need to be trained when seeking help because some of their habits are ineffective. Peter Liljedahl (2021) asserts that students seek help in many ways – some of which are counterproductive to learning. One such example is proximity help-seeking; questions that students ask when you are nearby. These requests are normally expedient: “am I doing this right?” or “what do I do?” In my experience, answering these questions is not helpful since it reduces independence and negatively impacts confidence. Sometimes a helpful action on my part is pointing a student to a peer who has made progress on a problem or encouraging them to “look it up.” While these approaches may sometimes seem cold or impersonal to the external observer, the goal is to build a culture of independence and resourcefulness in my classroom and my students, for the most part, understand this.

Presentation

Additional Resources

- Social network interaction and self-regulated learning skills: Community development in online discussions (Yen et al., 2022)

- Use of live chat in higher education to support self-regulated help-seeking behaviours: A comparison of online and blended learner perspectives (Broadbent & Lodge, 2021)

- Prior achievement in math impacts adolescents’ help-seeking behaviour in interactive learning environments (Cohen & Zusho, 2023)

- Ethical issues in educational technology (Aydin, 2024)

- Building thinking classrooms in mathematics, grades K-12: 14 teaching practices for enhancing learning (Liljedahl, 2021)

References

- Aydin, İ. (2024). Ethical issues in educational technology. Kastamonu Eğitim Dergisi, 861–881. https://doi.org/10.24106/kefdergi.1426735

- Broadbent, J., & Lodge, J. (2021). Use of live chat in higher education to support self-regulated help seeking behaviours: A comparison of online and blended learner perspectives. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 18(1), 17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-021-00253-2

- Cohen, R. L., & Zusho, A. (2023). Prior achievement in math impacts adolescents’ help-seeking behavior in interactive learning environments.

- Liljedahl, P. (2021). Building thinking classrooms in mathematics, grades K-12: 14 teaching practices for enhancing learning. Corwin Mathematics.

- Makara, K. A., & Karabenick, S. A. (2013). Characterizing sources of academic help in the age of expanding education technology: A new conceptual framework. In Advances in help-seeking research and applications: The role of emerging technologies. Information Age Publishing.

- Yang, F., Yang, X., Xu, M., & Stefaniak, J. (2024). An exploration of how students prioritize help-seeking sources in online learning environments. TechTrends, 68(3), 456–468. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-024-00944-3

- Yen, C.-J., Tu, C.-H., Ozkeskin, E. E., Harati, H., & Sujo-Montes, L. (2022). Social network interaction and self-regulated learning skills: Community development in online discussions. American Journal of Distance Education, 36(2), 103–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923647.2022.2041330