Prior to EDCI 568

Prior to the beginning of EDCI 568: Discourse on Social Media, I was deep in the trenches battling with my M.Ed project; it was a war of attrition and the paper was winning. Balancing work, school, and life has been particularly challenging this year with school work taking a back seat as I struggled to find balance. Up to that point, my project had been a collection of articles and some writing smashed together attempting to join them. Fortunately, while the aim was unclear, my problem was simple: why do low achieving students struggle with independent self-study? My experience as a teacher was telling me that it wasn’t as simple as a lack of desire to do well. Some of my struggling students very much want to succeed but cannot study by themselves productively – they are lacking a certain set of skills.

As it turns out, successful self-study is largely dependent on two factors: (a) self-efficacy and (b) self-regulated learning skills (SRL). The second factor, SRL skills, became the focus of my project and, let me tell you, the research was overwhelming. After a wee literature review, it became clear that I had to narrow my scope down to just one SRL strategy: help-seeking. The nature of help-seeking is complex since it is moderated by social interaction (Fong et al., 2023) and, therefore, difficult to generalize. Thankfully, Yang et al. (2024) were successful in categorizing help-seeking behaviour into three groups: (a) friend-seeking, (b) teacher-seeking, and (c) technology-dependent. The next stage in the project was to figure out how to design learning environments that facilitate help seeking according to these preferences.

Throughout open and online learning

In my professional context, I spend around 95% of my resources (time and energy) designing in person learning experiences. With the emergence of educational technology, classroom teachers like myself have been encouraged to add digital or online components to our classrooms. We are being asked to create blended learning environments so that students can seamlessly miss class or enjoy the freedom of a mixed modality. This creates a tension because many of us are not trained in online learning design so we are left to do what we think is best. Thankfully, through my experience in EDCI 568, I feel better prepared to design these online spaces through careful review of the literature and reflection on topics brought forward by experts in the field during guest lectures.

One such guest lecturer this term was Jesse Miller who shared some of the benefits of the internet and social media as well as the pitfalls or trouble areas associated with it. He mentions that multiple generations use social media to connect with friends and families for social interaction that would otherwise be impossible. At this point in our course, I had one question: can social media be used to connect students for the purpose of improving help-seeking behaviours? How can learning environments be designed that provide safe and effective avenues for help-seeking without dominating the in person learning space? The next step was to explore the ethical implications of social media use in school, especially for adolescents still in high school.

A good source for digital safety: https://www.getcybersafe.gc.ca/en

The first and most pressing issue with social media in K-12 education is digital safety. The Freedom of Information and Privacy Protection Act of BC (FOIPPA) requires students (or parents if the student is younger than 16 in BC) to provide written consent in the event that a course requires the use of a web-based tool where personal information is collected and stored on servers outside of Canada. Other issues that are more subtle include widening socioeconomic inequalities between students, the impact on childhood identity, and the negative effects on mental functioning and cognitive development (Aydin, 2024). This is typically the point where teachers quit on the idea of implementation of technology in the classroom because the dangers associated with it are not outweighed by the benefits. Thankfully, this project has given me an opportunity to explore the benefits and, if done in a safe and intentional way, can greatly outweigh risks.

Over the last 5 years, current literature suggests that online discussion forums are effective learning environments that enrich learning by connecting students and exposing them to other perspectives. By participating in online discussion forums, students experienced a greater sense of community with other learners (Yen et al., 2022) reached higher levels of cognitive presence (Al Mamun & Lawrie, 2024), and improved self-study through the use of technical and verification questioning (Lee et al., 2021). When students feel isolated in their study at home, online discussion forums can connect them with experts but without proper scaffolding or training, these environments can be intimidating.

An approach that balances digital safety and the benefits of connecting online would be to design an online learning environment that facilitates help-seeking, contains only students in a particular class, and is available during asynchronous study. This space would satisfy the digital responsibilities that we have as teachers when encouraging our students to use online tools while also satisfying their need for help during self-study. The last aspect to consider is the needs of the system and the needs of the overall community. In its simplest form, the system needs to provide connection between students without being overly burdensome. As for the community, heavy teacher moderation is required to ensure that the online space is respectful and help-seeking behaviours are productive (Smalley & Hopkins, 2020).

As we near the end

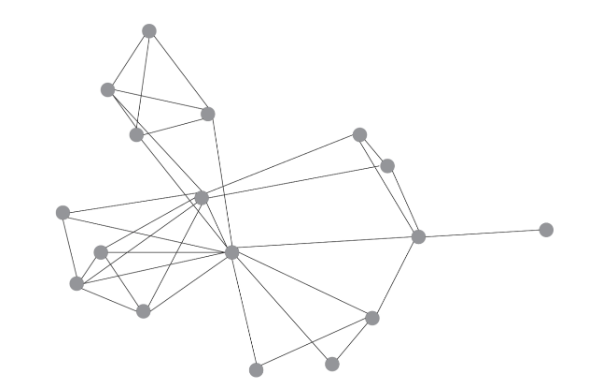

As the end of EDCI 568 draws near, I have been reflecting on the underlying nature of student connection for the purpose of help-seeking. A theoretical framework that describes this well is connectivism; the theory that learning is a network phenomenon that is improved by increasing the number of connections between nodes of information (Goldie, 2016). An example of how helping networks form is seen below:

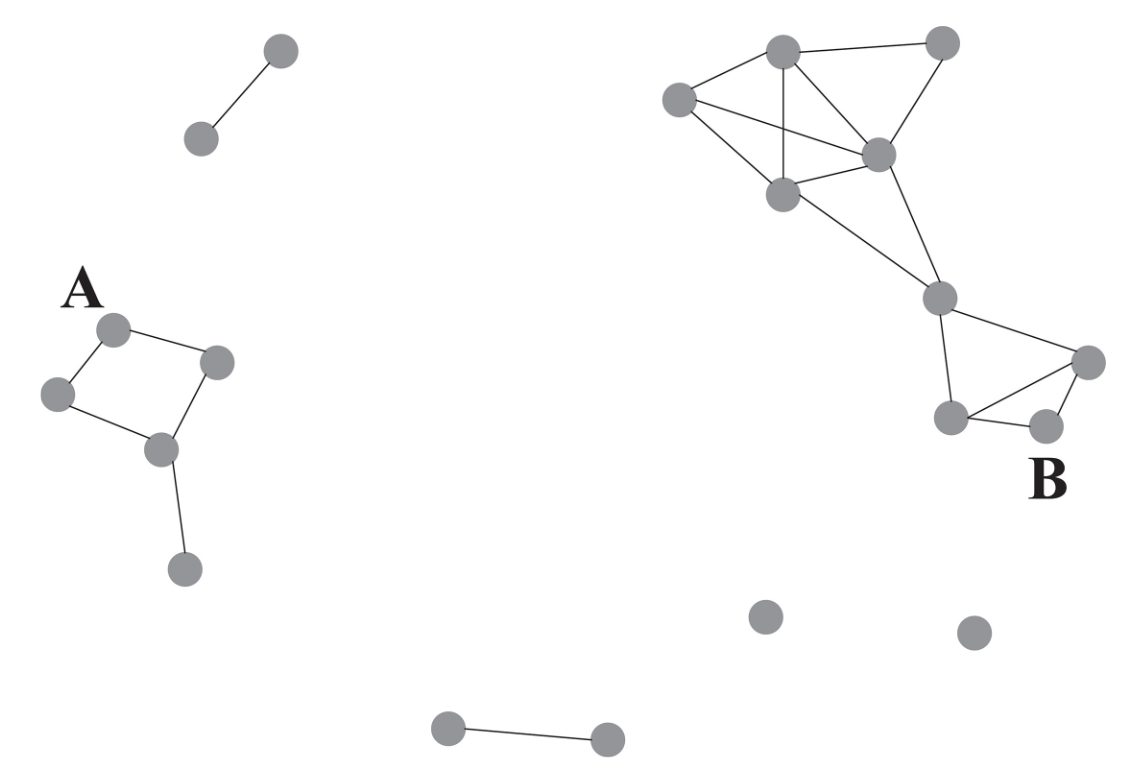

The nodes above represent students and the lines show their connection to other students. When a node (student) has many connections (lines), that means that they are well connected and seek help from a variety of sources. In contrast, the student on the extreme right has only one connection and likely requests less help than their peers. Van Rijsewijk (2018) found that learning networks like the ones above are ineffective since there is inequality in connection. They found that networks where everyone has roughly the same number of connections (below) provide better learning and help-seeking environments.

In the network above, students naturally segmented into two groups (A and B) with some other students either forming pairs or no connections at all. In their findings, segmentation did not significantly affect achievement while network inequality did. This means that students in group A and B are expected to achieve more since their number of connections is roughly the same in each of their respective groups (Van Rijsewijk et al., 2018). This is exciting as an educator since it informs how I think about group dynamics in my classroom. Before reading this, I may have encouraged my students to form as many connections as possible so the classroom can be fully connected. After reading this article, my focus has shifted to ensuring that each student is connecting to a group, even if the class is segmented.

References

Al Mamun, M. A., & Lawrie, G. (2024). Cognitive presence in learner–content interaction process: The role of scaffolding in online self-regulated learning environments. Journal of Computers in Education, 11(3), 791–821. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40692-023-00279-7

Aydin, İ. (2024). Ethical issues in educational technology. Kastamonu Eğitim Dergisi, 861–881. https://doi.org/10.24106/kefdergi.1426735

Fong, C. J., Gonzales, C., Hill-Troglin Cox, C., & Shinn, H. B. (2023). Academic help-seeking and achievement of postsecondary students: A meta-analytic investigation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 115(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000725

Goldie, J. G. S. (2016). Connectivism: A knowledge learning theory for the digital age? Medical Teacher, 38(10), 1064–1069. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2016.1173661

Lee, D., Rothstein, R., Dunford, A., Berger, E., Rhoads, J. F., & DeBoer, J. (2021). “Connecting online”: The structure and content of students’ asynchronous online networks in a blended engineering class. Computers & Education, 163, 104082. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2020.104082

Smalley, R. T., & Hopkins, S. (2020). Social climate and help-seeking avoidance in secondary mathematics classes. The Australian Educational Researcher, 47(3), 445–476. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-020-00383-y

Van Rijsewijk, L. G. M., Oldenburg, B., Snijders, T. A. B., Dijkstra, J. K., & Veenstra, R. (2018). A description of classroom help networks, individual network position, and their associations with academic achievement. PLOS ONE, 13(12), e0208173. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0208173

Yang, F., Yang, X., Xu, M., & Stefaniak, J. (2024). An exploration of how students prioritize help-seeking sources in online learning environments. TechTrends, 68(3), 456–468. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-024-00944-3

Yen, C.-J., Tu, C.-H., Ozkeskin, E. E., Harati, H., & Sujo-Montes, L. (2022). Social network interaction and self-regulated learning skills: Community development in online discussions. American Journal of Distance Education, 36(2), 103–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923647.2022.2041330