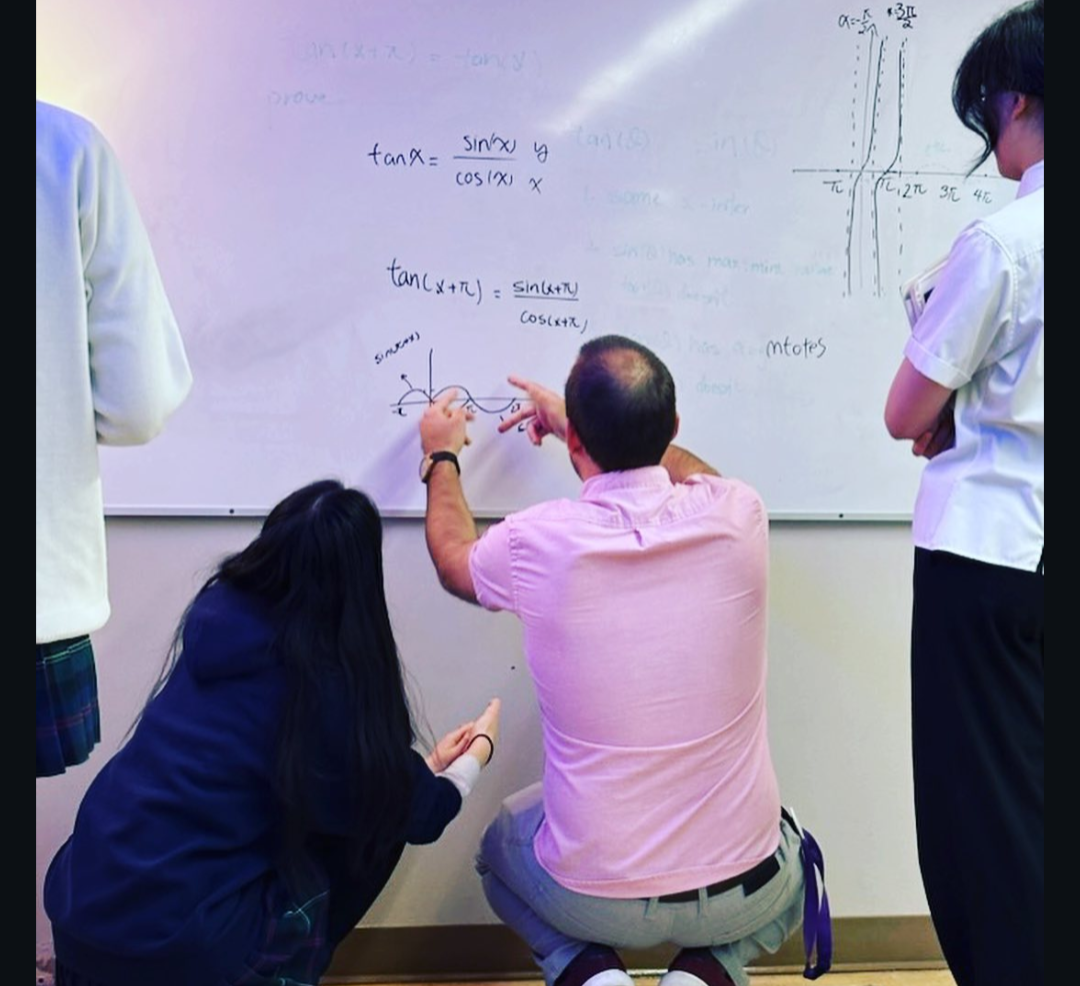

When reflecting on open education, whether that necessarily be online or not, I keep coming back to a personal inspiration of mine: the thinking classroom. For the uninitiated, BC mathematics educational guru Peter Liljedhal has pioneered a teaching technique called “the thinking classroom.” In short, this has students in small, random groups collaborating on vertical whiteboards to solve curricular mathematics problems. The goal of this technique is to encourage students to think rather than replicate. The focus is on increasing the amount of challenge students experience in the mathematics classroom while ensuring they feel supported by their peers rather than the teacher. In this system, the teacher takes on a questioning role rather than an authoritarian one so that students are encouraged to use their peers as a resource more than they otherwise would have.

While the ultimate goal of the thinking classroom is to promote thinking, there is an interesting byproduct of this approach: mobilization of knowledge. As students operate in the thinking classroom, they get a chance to work with new groups everyday which helps them build connections with their peers. After weeks (or months) of employing the thinking classrooms, something amazing happens: student begin to help each other across groups without being encouraged. They shift from board to board seeking out explanations about other approaches and bring them back to their group for integration. Astoundingly, this mobilization of knowledge persists even during other activities where the thinking classroom approach is not being used. During individual practice students ask each other questions frequently before they even look at me. Project work becomes easier to facilitate because students are already comfortable with each other and have become competent accepting challenging perspectives.

This mobilization [maybe a reference for the effect of knowledge mobilization] transforms the learning experience in a classroom since, rather than waiting for a teacher to become available for help, students can make use of the other nodes of knowledge in the classroom. Teachers can get the best bang for their buck by explaining a concept to one student and watching it spread through that freshly created expert to the novice student. Rather than have one educator in the classroom, mobilization can make teaching assistants out of the stronger students and improve the student-teacher ratio for the weaker ones. The beauty of this perspective on classroom teaching is the fluidity it provides; a student strong in one concept might be weak in another – this provides previously weak students a teaching opportunity. In any learning environment that successfully achieves mobilization of knowledge, any student on any day can take on the role of teacher depending on their level of comfort with the concepts. This allows historically successful students to take a back seat every once in a while while low confidence students can improve their self-efficacy.

Connections to my M.Ed Project

Knowledge mobilization is like a house plant; care for it and watch it grow, neglect it and watch it wither. For 210 minutes a week I try to encourage knowledge mobilization amongst my students for two reasons: (1) students learn best when engaging with their peers and (2) one day they won’t have me to facilitate their learning for them. One way students flex their agency in the classroom is to seek help from their peers – a major focus of my M.Ed project. The goal of my research is to extend knowledge mobilization (or help-seeking) to an online and asynchronous learning platform similar to stack exchange. This is necessary in mathematics because the lowest performing students are often the ones that are least able to study independently due to anxiety, low self-efficacy, or a feeling of isolation in their learning. The central question of my research is “how do we connect students – both high and low achievers – to facilitate help-seeking behaviors and improve self-regulated learning strategies?”

The situation that educators today are trying to avoid is one where we do everything for our students. It is easy for us, with all of our lived experiences, to identify students who are struggling and connect them with the help that they need. While this might be appropriate for our youngest learners, it does very little for our older students who are on interface between high school and post-secondary. Our role shifts from authoritarian to guide – how can I help my students seek help for themselves? It is easy to say that, these days, students enjoy a wide and complex network of information housed neatly within the internet. Unfortunately, the information suffers from three ailments when used in a specific educational context (like math or social studies) – it varies in credibility (AI), it is hard to contextualize, and much of it is irrelevant. This, coupled with the importance of socialization in youth, make it clear that an important tool in a student’s toolbox is making use of a learning network consisting of their peers.

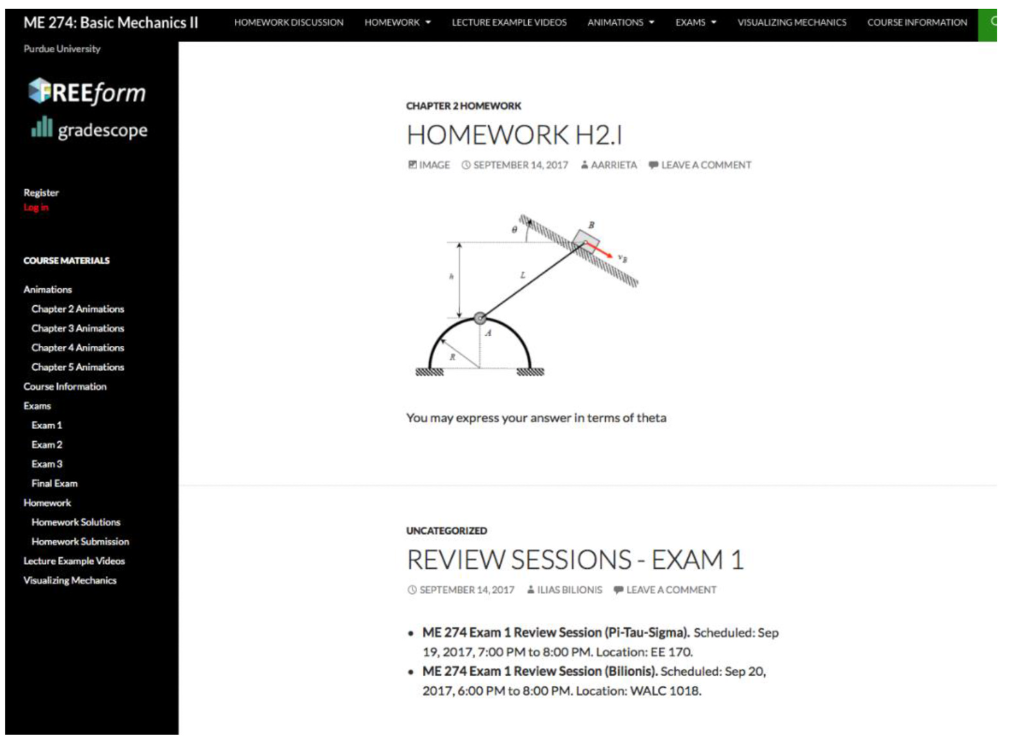

On the assumption that help-seeking behavior is efficacious for many aspects of life such as learning and mental health, we can dive into the meat of my project – can online platforms be used to facilitate help-seeking in youths? Enter Lee at al. (2021) and their paper titled “Connecting online: The structure and content of student’s asynchronous online networks in a blended engineering class:” a study focusing on how text-based computer-mediated communication environments can be used to allow individuals to interact with each other without time or place restraints. Students with ample self-regulatory skills already make use of spaces like this – reddit and stack exchange to name a few a hotbeds for collaboration surrounding STEM subjects. But the target of my research is not the high fliers, it is the students with the lowest achievement in math – students with very little ability to seek help from their peers and often find themselves isolated.

Without diving too deep into the details of Lee et al.’s (2021) study, I will avoid the wall of text and provide some of the key findings in bullet form below:

- The majority of students in online discussion forums ‘lurk’ meaning they passively view content without contributing to discussion.

- Knowledge collaboration still occurs on online forums even when participation is low.

- Online discussion forums should be moderated by instructors to show students the best way to collaborate with one another.

- Robust online discussion forums serve high achievers (they tend to ask highly technical questions) as well as lower achievers (they tend to solicit general advice or ask clarifying questions).

In just this study alone, it is clear that online forums can be an effective medium for improving the collaborative nature of a physical classroom by servicing both high and low achieving students. What is clear is the need for careful design and constant moderation of the platform. These online environments do best when they are taken care of by the instructor and made an inseparable part of in-person courses. Students will ultimately make use of these platforms if there is reason for them to do so. A starting place would be to make participating in these environments part of the overall course grade but, eventually, the hope is that they chose to make use of these online forums because they supplement and enrich their learning.

References

Lee, D., Rothstein, R., Dunford, A., Berger, E., Rhoads, J. F., & DeBoer, J. (2021). “Connecting online”: The structure and content of students’ asynchronous online networks in a blended engineering class. Computers & Education, 163, 104082. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2020.104082