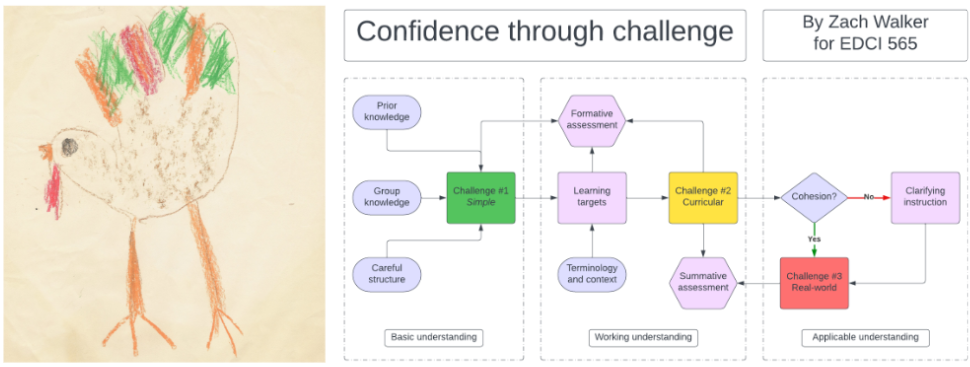

As a 31-year-old person who has spent over two-thirds of their life in some educational institution, I have many learning experiences to ruminate on, compare, and draw inspiration from. From creating “hand turkeys” in Kindergarten for Thanksgiving to crafting a visualization of how I design learning experiences for my students at St. Margaret’s, the tasks might vary in complexity, but the goal is all the same: learn something. In some tasks, we need to learn new skills (the former) and in others, we need to learn something metacognitive about our internal processes (the latter). Both are valuable and both are necessary.

When asked to reflect on what I regard as my best-structured learning experience (either as a teacher or a student), a thousand ideas filled my head but only a few made my heart ache with longing. One of those painful-because-cathartic experiences occurred at the University of Victoria in the Indigenous education faculty in the summer of ’21. What made this experience memorable was the extremely unique setting (or place). Indigenous education is deeply rooted in place and while we could not be present, together, in place (COVID), we could still be together via technology. This allowed for the exhibition and integration of many places as students were scattered all about Canada which led to a unique learning experience not possible with traditional all-in-same-place activities.

Now, without further delay, I present to you one singular learning experience from that summer for our dissection, analysis, reflection, and integration: drum-making. In typical Western education, the process of making a drum is rather straightforward:

- Your teacher provides you some historical or technical context relating to drums and/or drum-making.

- Your teacher gives you all of the materials needed to create the drum.

- Your teacher demonstrates each process of drum-making while you follow along.

- Your teacher shows you pictures of completed drums and gives you the artistic freedom to decorate them as you see fit.

The process we followed with UVic’s Faculty of Indigenous Studies was very similar to the Western structure above but with one small but impactful difference: we were not permitted to keep our drums after we completed them. A subtle aspect of Indigenous teaching was present from our first day when our instructor shared this with us. We were told that in Indigenous culture, the first drum you make is given to someone you love. This utterly transformed the process and shifted our western perspective of production to something else entirely.

The intended outcome of this course was not to make a drum. It was to design something for someone that you love when drum-making was simply a medium for expression. The drum above was made for my father and signifies our shared history centreing around our love for the ocean. Can you recognize the islands pictured in the centre of the drum?

Questions like “how can I best stretch the hyde over the loop?” and “to what tension produces the best tone?” were replaced with questions like “how will the design honour my love ones” and “how will I know when it is ready to gift?” This is one of the most subversive aspects of Indigeneous culture that I have experienced; the lesson is rarely in the task, but rather, the story.